For this second post, I wanted to write about a percussion instrument that is closer to home while learning a little more about my own culture and heritage. The instrument in question is the Buk (북), a traditional Korean drum that is shaped like a “double-headed” barrel, meaning that there are two stretched membranes covering each end (figure 1).

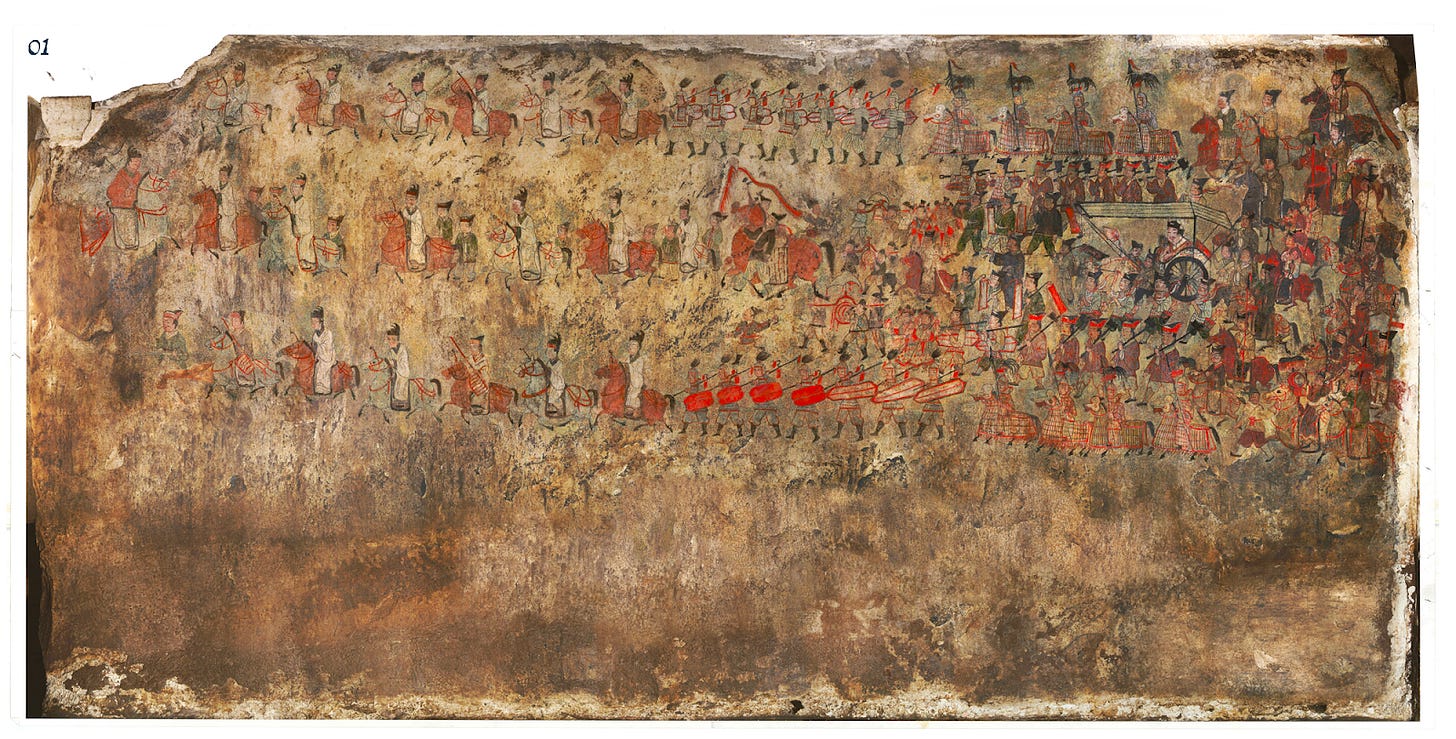

Historians suggest that the Buk has held a significant role in Korean culture since the period of the Three Kingdoms of Korea (57 BC to 668 AD). Illustrations of Buk drums were found on murals in ancient tombs from this era, which often honoured important political figures. “Anak Tomb No. Three” is one of the most remarkable burial sites of the Koguryo kingdom, situated in the north of the peninsula, which contains various mural paintings with dated inscriptions aimed at displaying the “national strength and high cultural status” of this society.1 It has been dated to approximately 357 from the epitaph.

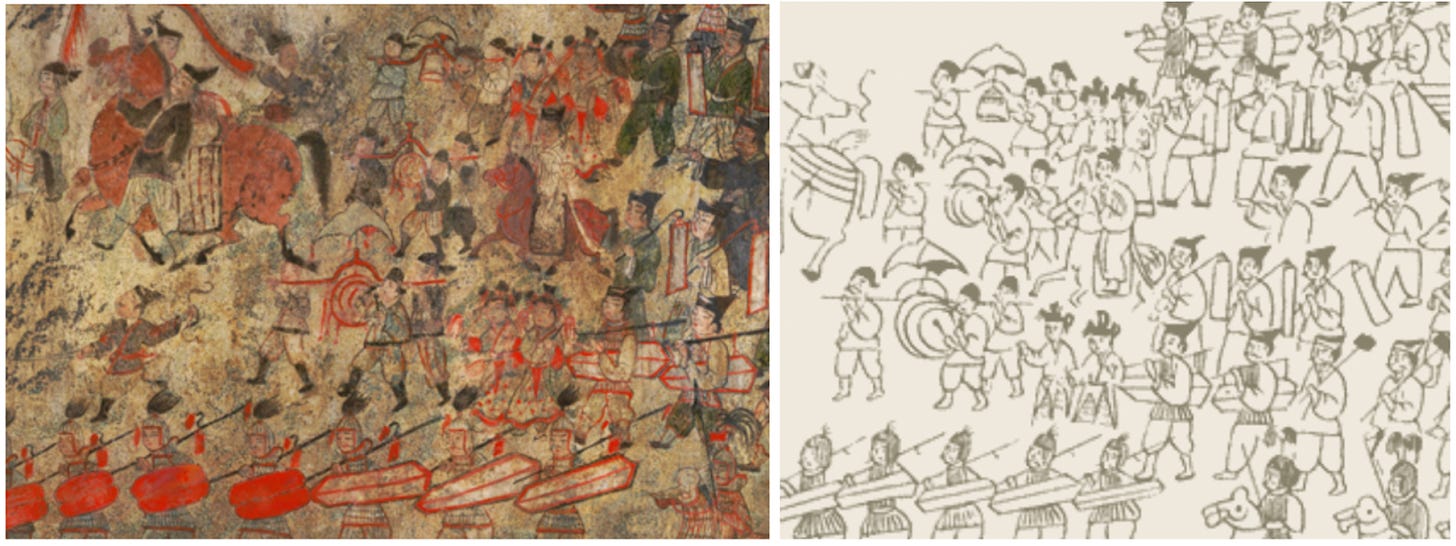

One of the paintings in this burial site, which can be found on the east wall of the corridor depicts a procession of approximately two hundred and fifty people accompanying the owner of the tomb, who can be seen sitting in the wagon near the top right-hand corner (figure 2). Interestingly, the painting depicts this moment from a bird’s eye view, allowing for a clear visual arrangement of the procession in parallel rows. The abundance of people consists of buk-players (figures 3-4), horsemen, flag-bearers, armed soldiers and servants, all of whom are clearly visible because of the painting’s immense size of two by ten and a half metres.2 This mural is a very valuable historical record of mid-fourth century Korean society as it portrays a visual glimpse of the past and demonstrates the crucial role of the buk in cultural rituals.

As the appearance of the buk may seem very simple and straightforward, its cultural and historical significance may be misunderstood and underestimated. However, hearing the sound of this ancient drum can give the listeners an auditory glimpse into the past and take them back in time, allowing them to sensorially imagine what this procession scene might have been like (see video 1).

There are many different types of buk drums that are played in different contexts, such as the sori buk (소리북), used to accompany ‘pansori,’ which is a genre of Korean musical storytelling performed by a singer and drummer (figure 5). This traditional musical art dates back to the Joseon Dynasty in the seventeenth century, and is characterised by performances of ‘expressive singing, stylized speech, [and] a repertory of narratives and gestures’ that can last up to eight hours and which combine folk and erudite literary expressions.3 Pansori often conveyed and strengthened religious values, and in particular through traditional Korean shamanic songs and folktales, in addition to exploring moral ideas about community and the importance of social cohesion.4 Since 1964, Pansori has been recognised as the fifth Korean National Intangible Cultural Heritage. In addition, in November 2003, Pansori was celebrated as UNESCO’s Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity of Korea.5

Moreover, there is also the pungmul buk (풍물북) which differs from the sori buk because its body is tied together with strings rather than nickel ornaments of molten metal.6 This allows the pungmul buk to create a strong and firm sound, and to perform ‘nongak, an amusing style of music played in farming regions.'7 Unlike the sori buk, the pungmul buk also has a fabric strap, which allows the performer to support it on their shoulder while walking around. The depth and clarity of the drum’s sound originates with the process of its very making; as for the pungmul buk, paulownia tree wood or cotton wood is used for the body of the drum, which is hollowed out from a block, and bullhide or horsehide for the membrane. On the other hand, the sori buk, used in pansori performances, is assembled with various pine wood pieces glued together, and has a membrane of bullhide that is fixed with nails, rather than ropes like the pungmul buk.8

Figure 5: Pansori performed by one singer and drummer. Intangible Heritage Digital Archive.

This video below demonstrates examples of both indoor and outdoor pansori performances. Learning about the history of buk and pansori has allowed me to realise the full strength and power of drums, as it is shown through the art of pansori how melodic and significant they can be even if untuned.

Lena Kim, Ed. “Representative Tomb Murals: Anak Tomb No. 3,” Koguryo Tomb Murals (ICOMOS Korea) https://jikimi.cha.go.kr/english/heritage_book/korguryo.pdf.

Ibid.

“Pansori Epic Chant,” UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/pansori-epic-chant-00070#:~:text=Pansori%20is%20a%20genre%20of,both%20elite%20and%20folk%20culture, accessed October 22 2023.

Kang, Bomi, "Pansori" (2016). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2789.http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/9302946, https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3790&context=thesesdissertations, accessed December 13, 2023

“Pansori Epic Chant,” UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/pansori-epic-chant-00070#:~:text=Pansori%20is%20a%20genre%20of,both%20elite%20and%20folk%20culture, accessed October 22 2023.

Kim San-Hyo, “Buk,” Arts Council Korea, https://www.igbf.kr/DataFiles/App/PDF/buk_en_link.pdf, accessed October 22 2023.

Ibid.

Ibid.